James Rick: "A Little Legislative Tinkering"

A Little Legislative Tinkering:

Repairing the Legal Rights of Farmers to their Machines

James Rick, Ph.D. candidate at the College of William & Mary

Our latest installment in our series of web-based essays analyzes the effort to legislate the "right to repair." The author, James Rick, is a Ph.D. candidate at the College of William & Mary. We welcome essays that apply the stories and methodologies of our allied fields to the issues that currently affect our daily lives. If you are interested in contributing, please contact Adrienne Petty at ampetty@wm.edu.

It should be cited as: James Rick, “ A Little Legislative Tinkering: Repairing the Legal Rights of Farmers to their Machines,” The Short Rows, November 2, 2020. https://www.aghistorysociety.org/ahs-blog/rick-a-little-legislative-tinkering

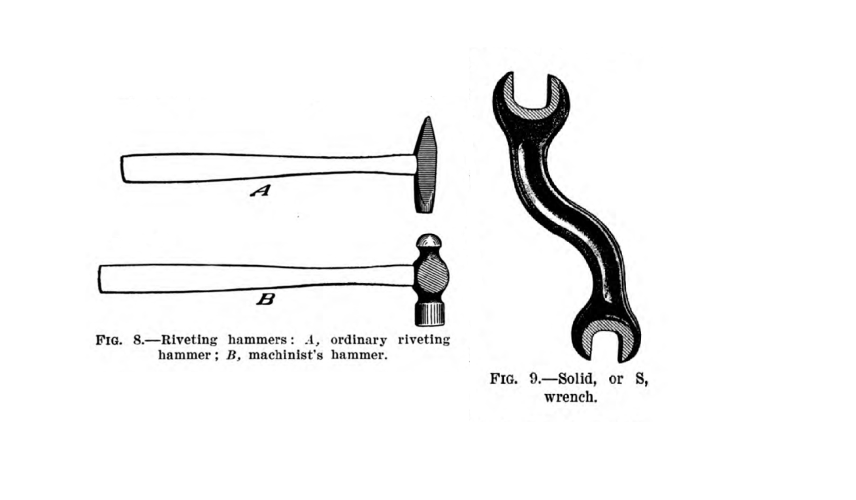

"A few tools of farm machine repair."

Source: W. R. Beattie. The Repair of Farm Equipment. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers' Bulletin 347. (Washington: GPO, 1909), 12.

In the months before the 2020 Democratic primaries, conversations about the “Right to Repair” brought a piece of agricultural and technological policy to the national spotlight. The “Right to Repair” involves legislation that would allow the users of complex technological equipment—like the farmers who cultivate and harvest with large combines and other agricultural machinery—to repair that equipment themselves or to seek repair services from parties other than the equipment manufacturer. In a 2020 primary that also included Andrew Yang, whose campaign was framed around the social problems likely to emerge out of the “fourth industrial revolution,” heavier contenders from the left wing of the Democratic party, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, both brought an anti-monopoly angle to their approach to agricultural and technological policy. This call for a “Right to Repair” in a digital age conjures America’s agricultural past and the relationships between farmers and their machines at the dawn of what many 19th-century Americans dubbed “the machine age.” Since the middle of the 19th century, machine repair has been an important part of farm life and labor as well as an arena in which they have experienced American capitalism.

My dissertation research concerns the efforts of rural people in ensuing decades to build practices of machine use that fit farm machines into the technological, social, and environmental systems in which they lived. Mechanical reapers, mowers, and threshers began to become a feature of Northern farms in the 1840s. Farming people incorporated these machines into their systems of labor organization and found ways to work around the limitations placed on horse-drawn machines by hilly fields and other environmental obstructions. They also built practices of machine maintenance, and my work is inspired by scholars who have recently sought to put maintenance at the center of the history of technology. As farming people mended a harvester reel or sharpened the blades of their reapers, they made machine repair a central farming activity. 19th-century farmers’ practices of machine use and maintenance were shaped by, and in response to, farmers’ position in the structures of 19th-century capitalism. While the purchase of machines often meant that these farmers had to take on debt, their dedication to, and knowledge of, machine maintenance allowed them to avoid some of the risks of that debt.

It was the structures of 21st-century capitalism, on the other hand, that Sanders and Warren addressed when they both proposed “Right to Repair” laws—a concept that has begun to garner attention on the state level in recent years. Massachusetts led the way in 2013 when voters overwhelming approved a measure to require that auto manufacturers make data from vehicles’ diagnostic systems available to car owners and independent repair shops, allowing those owners and shops to make repairs to any number of vehicle components that interact with the car’s digital systems. Without access to that diagnostic information, or without the ability to alter the vehicle’s software, drivers and mechanics might have no choice but to rely on the manufacturer’s own dealer shops for repairs. Another ballot measure to close a loophole in the Massachusetts law is back up for a vote this November, and many other states have begun considering these policies in the past few years.

In our world of increasingly complex information systems, the machines we use every day are dependent on lines and lines of code. Sometimes that code is proprietary and protected by patent law, but in other situations it is simply designed in such a way that the ordinary computer of an owner or independent mechanic cannot access it. This technological illegibility benefits manufacturers at the expense of consumers and mechanics. There is a parallel story in the cell phone industry, where the price of repairs is driven so high by technological and proprietary restrictions that consumers will often simply opt to replace a phone rather than repair it. The broken, but fixable, phone might still find its way back to another consumer, but not without cycling back through the manufacturer, carrier, or insurance company with a markup. As everything from cars to homes are made “smart,” the control over the entire lifecycle of the everyday machines we all use will likely shift more and more into the hands of the corporations who control the code.

The discussion about the “Right to Repair” has touched a number of industries, but there is significance to the fact that it was in the interest of farmers, in particular, that the two Senators initially announced their “Right to Repair” positions. Their proposals would have mandated that manufacturers of farm machinery, like John Deere and Case International, make the diagnostic information of farm machinery available to farmers and independent mechanics. These companies are, like auto-manufacturers, increasingly in the business of software, as well as hardware. They sell the software internal to the machines that allows them to function as well as software—like John Deere’s “Precision Ag” packages—meant to integrate fields and crops into a world that can be understood, displayed, and manipulated through computer systems. As the vendors of digital products and services alongside material ones, these companies find themselves in a similar position to the manufacturers of cars or even smart phones. Opponents of the concept in an agricultural setting have therefore taken similar positions to the opponents of previous iterations of the “Right to Repair” that focused more on cars. They argue that the “Right to Repair” would principally benefit bad actors and data thieves at the expense of companies whose efforts to bring “Big Data” into agricultural technology can only benefit farmers. Sanders and Warren, however, saw the effort to allow farmers to repair their own farm machines, or to patronize any independent mechanic they wished, to be an important part of their stance against corporate power in agriculture during the primary election cycle.

Nineteenth-century farming people also found themselves in new relationships with the large firms of emerging corporate capitalism. They purchased machines on credit, sometimes from large firms like McCormick and Deering who would go on to form the International Harvester Company in 1902. They also relied on manufacturers to some extent for repairs and repair parts, but the knowledge of machines they cultivated allowed them to nonetheless handle a lot of maintenance and repair work themselves. Those manufacturers, for their part, recognized that farmers valued their ability to repair their machines, as the makers of everything from the mechanical reapers and threshers of the 19th century to the tractors of the early 20th century, advertised the fact that their machines could be quickly repaired by farmers themselves.

Repair was also embroiled in 19th-century farmers’ conflicts with the growing power of large manufacturing firms as well. In the midst of the Granger movement of the 1870s, machine manufacturers resisted the efforts of the Patrons of Husbandry (also known as the Grange) to do away with the “middleman”—the sales agents and dealers of those companies—in part on the grounds that their agents were necessary to get machines started and to keep them in good repair in farmers’ fields. Farmers claimed repair as a political tool as well. One farmer, in the time of Farmer’s Alliances and on the eve of the Populist movement, wrote to the Prairie Farmer on January 17th, 1891 to encourage his fellows not to buy machines from a recently formed “Harvester Trust,” because “the same machines that did the work in 1890, if they were properly taken care of, will do the work of 1891, 1892 and 1893, and longer with some repairs.” He saw maintenance as a strategy to be used against monopoly power. Throughout their lives, labors, and struggles over the second half of the 19th century, farming people became maintainers of their machines and sought to shape their technological world to their own ends.

In our time, the interest in policy that might help the users of important technologies to claim ownership of them, without the restrictions that data can be used to impose, is one form that the struggle for control of our human-built world can take. “Right to Repair” has largely fallen off the campaign trail since the exit of Sanders and Warren from the presidential race. Democratic nominee, Joe Biden, has so far stopped short of adopting his former rivals’ more stringently anti-monopolist positions on agriculture and technology, including the “Right to Repair” for farm machines, and while the Trump Administration’s Federal Trade Commission (FTC) hosted a workshop on “Right to Repair” possibilities in July 2019, the issue does not seem to have garnered much attention in an eventful election cycle. There are certainly reasons to think that the push may continue to come from America’s farmers. The historical narratives and cultural symbolism of independent, self-sufficient farmers and the history of confrontation with corporate power lend themselves to a conflict against an enforced dependence on corporations. As the state-level debates continue—whether the conversation is about farm machines, automobiles, or cell phones—we will likely see further questioning of just how independent any American can be in a digital world in which the data and software belongs to a few corporations.

A Few Web Sources:

Andrew Yang 4th Industrial Revolution: https://slate.com/business/2019/10/andrew-yang-fourth-industrial-revolution.html

Sanders Agricultural Policy: https://www.politico.com/story/2019/05/05/bernie-sanders-agriculture-rural-policies-1302634

Warren Agricultural Policy: https://www.politico.com/story/2019/08/07/how-elizabeth-warren-plans-to-reboot-the-farm-economy-1450796

Warren on Right to Repair: https://www.theverge.com/2019/3/27/18284011/elizabeth-warren-apple-right-to-repair-john-deere-law-presidential-campaign-iowa

Sanders on Right to Repair: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/8xzqmp/bernie-sanders-calls-for-a-national-right-to-repair-law-for-farmers

General Articles on Right to Repair, especially on the state level:

Massachusetts Right to Repair: https://ballotpedia.org/Massachusetts_Question_1,_%22Right_to_Repair_Law%22_Vehicle_Data_Access_Requirement_Initiative_(2020)

New York Times article on the Right to Repair: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/23/climate/right-to-repair.html?utm_source=pocket-newtab

A rural Republican Congressman’s opinion against Right to Repair: https://www.realclearpolicy.com/articles/2020/03/20/right_to_repair_is_about_stealing_tech_not_helping_farmers_487046.html

A Letter to the Editor against the Right to Repair in Progressive Farmer: https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/columns/letters-to-the-editor/article/2020/02/18/fair-repair-legislation-farmer-led

Right to Repair advocate responds to the above in Progressive Farmer: https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/columns/letters-to-the-editor/article/2020/02/19/fair-repair-legislation-farmer-led

Another Article in Progressive Farmer from 2016 about proposed Nebraska Legislation: https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/equipment/article/2016/08/04/fair-repair-act

Comment given by John Deere to the Copyright Office: https://copyright.gov/1201/2015/comments-032715/class%2021/John_Deere_Class21_1201_2014.pdf

Bloomberg Article that discusses John Deere’s “Precision Ag” and “Right to Repair”: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-03-05/farmers-fight-john-deere-over-who-gets-to-fix-an-800-000-tractor

The Maintainers Blog: https://themaintainers.org/

Joe Biden Agricultural Policy: https://www.politico.com/story/2019/07/17/joe-biden-agriculture-rural-2020-1598121

Trump’s FTC Workshop on Right-to-Repair: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/events-calendar/nixing-fix-workshop-repair-restrictions